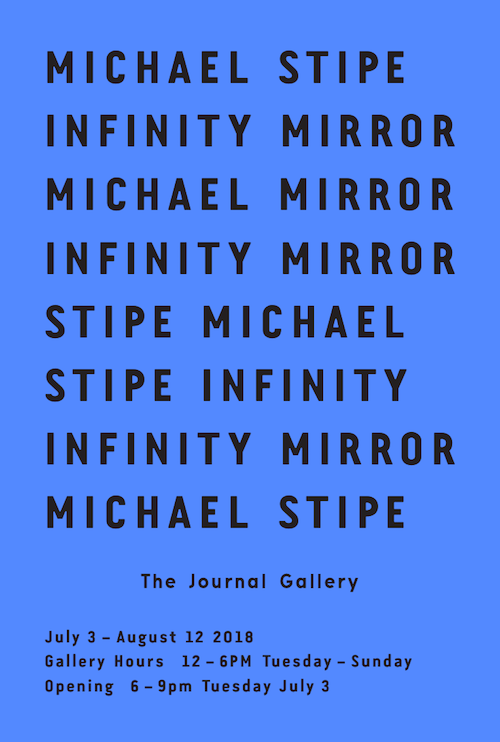

The Journal Gallery in Williamsbug might just get busier this summer as they launched “Infinity Mirror,” a solo exhibition by ex-R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe, organized by Clarissa Dalrymple.

“Infinity Mirror” stems from the contents of Stipe’s recent publication, Volume One, and further expands on his use of photo-based practices to explore the 1970’s as a formative decade through its cultural impact on his coming of age, and subsequently, the manner in which its influence informed the creative work he went on to create, both privately and as a public figure.

The exhibition presents a selection of photographic material, ranging from images made by Stipe, to historical ephemera he continues to collect and alter, or use as source material that informs his own use of the camera. These found and made materials remain in an ongoing and ever-shifting relationship within Stipe’s practice, blurring understandings of time and authorship.

In the gallery, four distinct bodies of work are positioned as facets of the piece Infinity Mirror, 2018. Situated in the center of the space, this work functions as a lexicon of sorts. It is comprised of ten identical brass shelving units by the iconic 1970s designer Milo Baughman, which Stipe has aligned edge to edge, creating an object of unusual volume and density, appearing as a multiplying projection of itself. The sculpture displays an eclectic collection of both personal and historical ephemera, including keepsakes and materials that Stipe encountered firsthand as a teenager.

Andy Warhol, for example, features prominently in Infinity Mirror as a connector, appearing first through one of his original large-format Polaroid Big Shot cameras, which sits shelves away from a 1977 photograph of Roy Cohn’s 50th birthday party, in which Warhol is seated next to Cohn, staring directly at the camera. These pieces sit across the room from a 1985 Todd Eberle photograph, documenting the only time Warhol and Stipe met.

Another unit is devoted to the artist Jeremy Ayers (1948-2016), Stipe’s mentor and self-described first love, with whom he remained close throughout Ayers’ life. Much as Infinity Mirror provides a kaleidoscopic period lens for the exhibition, Stipe locates Ayers as perhaps its most significant singular point of origin, weaving a remarkable web connecting the personal, cultural, and historical threads in the exhibition.

The collection of objects which populate the Baughman unit devoted to Ayers range from recreated arrangements of curiosities, that Ayers himself assembled in his home, to a small monitor playing Stipe’s video Jeremy Dance, a collaboration between the two, created in 2014. A small, manipulated photographic self-portrait, depicting Ayers in his drag persona Sylva Thinn (circa 1971), hangs adjacent to a portrait Stipe took of Ayers cloaked in vines in his apartment in Athens, Georgia, shortly after they met in 1979.

Many of the autobiographical photographs, which comprise another major body of work included in the exhibition, document the creative community in Athens, Georgia, that Stipe was introduced to by Ayers, and to which they both continued to contribute, as it developed throughout the ‘80s, ‘90s and 2000s. The aesthetic sensibilities which Stipe attributes to Ayers’ mentorship also trickled down into popular culture in fractured form, through Stipe’s friendships and mentorship of younger public figures, notably the actor River Phoenix and the musician Kurt Cobain, both of whom are the subject of photographs in the exhibition.

A diaristic body of work, which draws on 750 contact sheets of photographs taken between 1979 and 2013, constitutes one half of a large-scale diptych. Two side-by-side, floor-to-ceiling wheat-pasted Xerox wallpapers serve as a backdrop for the piece, with the aforementioned archival photographs presented against an outtake from Stipe’s shoot for the cover of R.E.M’s first album, Murmur. The image that was chosen for the record, becoming ubiquitous in the 1980s, is infamously empty, showing only a field of kudzu, a wild vine known for its rapid overgrowth, which is now native to Athens, Georgia. However, the majority of the images from this shoot included Stipe’s sister Lynda and Jeremy Ayers, who had accompanied him. As much as these works offer a deeply personal autobiography, they also have the potential to radically alter our understanding of an iconic image in popular culture.

The left side of the diptych—both the wall-sized image and the numerous, exclusively male nude, photographic works hung directly on top of it—borrows poses from historical photographs and objects that informed the evolution of Stipe’s largely idiosyncratic notion of queerness and masculinity.

The manner in which these works are presented is also emblematic of Stipe’s particular relationship to the materiality of photography—one which favors non-precious modes of printing, often associated with popular formats or mass production, incorporating properties of both the machine and handmade, analog and digital.

Throughout the exhibition, Stipe’s conflation of figures in his own life with those in history and popular culture, creates a particular synchronicity, where the formal qualities or provenance of images and other materials in the exhibition often rhyme and relate in a poetic or lyrical way, allowing for unlikely juxtapositions and connections to emerge between subjects. These democratized relationships transcend logical associations between time, place, and social structures, instead revealing unknown histories or suggesting more complex understandings of a given subject.