Nearly five decades since his debut LP, Jackson has announced his latest album, Downhill From Everywhere, set for release July 23.

“Songwriting is a mysterious thing,” says Jackson Browne. “Sometimes it feels a bit like consulting the oracle.”

Take a listen to ‘Downhill From Everywhere,’ Browne’s first new album in six years, and you might begin to suspect that he’s speaking quite literally. Though the songs here were recorded prior to the tumultuous events of the past year, the collection feels remarkably prescient, grappling with truth and justice, respect and dignity, doubt and longing, all while maintaining a defiant sense of optimism that seems tailor-made for these turbulent times. Like much of Browne’s illustrious catalog, ‘Downhill From Everywhere’ is fueled by a search—for connection, for purpose, for self—but there’s a heightened sense of urgency written between the lines, a recognition of the sand slipping through the hourglass that elevates the stakes at every turn. “Time rolling away, time like a river, time like a train,” he sings. “Time like a fuse burning shorter every day.” And while such ruminations might suggest a meditation on aging and mortality from a rock icon in his early 70s, the truth is that Browne isn’t looking in the mirror; he’s singing about us, about a world fast approaching a social, political, and environmental point of no return. Clean air, fresh water, racial equity, democracy—it’s all on the line, and nothing is assured.

“I see the writing on the wall,” says Browne. “I know there’s only so much time left in my life. But I now have an amazing, beautiful grandson, and I feel more acutely than ever the responsibility to leave him a world that’s inhabitable.”

While the issues Browne tackles on the album are often sweeping and existential, he writes on a far more intimate scale, consistently zeroing in on the human experience at the heart of it all. Whether singing about a Catholic priest navigating the slums of Haiti on his motorbike or a young Mexican woman who’s risked everything in pursuit of a better life across the border, Browne manages to tap into a universal emotional language, one that makes the old feel new and the foreign feel familiar.

“There’s a deep current of inclusion running through this record,” Browne explains. “I think that idea of inclusion, of opening yourself up to people who are different than you, that’s the fundamental basis for any kind of understanding in this world.”

Indeed, that kind of profound empathy has been at the core of Browne’s work for more than 50 years now. Hailed as one the Greatest Songwriters of All Time by Rolling Stone, Browne got his start behind the scenes, penning tunes that would be recorded by the likes of Nico, The Byrds, and Tom Rush before launching his own solo career with his classic 1972 self-titled debut. Known for era-defining hits like “Running On Empty” and “The Pretender,” as well as deeply personal ballads like “These Days” and “In the Shape of a Heart,” Browne would go on to sell more than 18 million records in the US alone and be inducted into both the Rock and Roll and Songwriters Hall of Fame. Throughout his career, Browne also regularly threaded activism into his life and songs, raising funds and awareness for social, political, and environmental efforts.

Despite his success, Browne’s never been one to rest on his laurels, and as ‘Downhill From Everywhere’ proves, he’s still pushing himself some 15 albums into his storied career. Recorded with a core band that included guitarists Greg Leisz (Eric Clapton, Bill Frisell) and Val McCallum (Lucinda Williams, Sheryl Crow), bassist Bob Glaub (Linda Ronstadt, CSNY, John Fogerty), keyboardist Jeff Young (Sting, Shawn Colvin), and drummer Mauricio Lewak (Sugarland, Melissa Etheridge), the record is a truly collaborative work, one driven by group chemistry and an openness to new sounds and ideas.

“Lately, I find that much of the writing process takes place in the studio,” says Browne, who also produced the album. “The music is informed by the way that everyone interacts with it in the room, and there’s this journey of exploring and cutting and re-cutting that can lead you to places you never would have ended up at on your own.”

That’s certainly the case with buoyant album opener “Still Looking For Something,” which has been percolating in Browne’s subconscious for years. Balancing wit and wisdom, it’s an ode to freedom wherever we can find it, and it serves as the perfect introduction to a record that, time and again, answers darkness and doubt with redemption and resilience. The playful “My Cleveland Heart,” for instance, imagines the liberation that would come from replacing our fallible, human hearts with unbreakable, artificial ones (“They’re made to take a bashin’ / And never lose their passion”), while the bittersweet “Minutes To Downtown” summons up the courage to take a leap of faith with someone who changes your entire world. “No I didn’t think that I would ever feel this way again,” Browne sings on the track. “No, not with a story this long and this close to the end.”

“On the surface, it’s about living in LA,” he explains, “but it’s really a metaphor for life itself. I adore this city, but I’ve been trying to leave since around the time I finished my first album. You can love and appreciate and depend on a life as you know it, but deep down, you may also long for something else, even if you don’t know what it is.”

That longing drives many of Browne’s characters on the album. The tender “A Human Touch”—a co-write with Steve McEwan and Leslie Mendelson, who shares the vocal with Browne on the exquisitely beautiful duet—grapples with the discrimination that still surrounds same sex relationships, tapping into the universal desire for love and connection and understanding that flows through us all, regardless of our orientation. “The Dreamer,” meanwhile, follows a Mexican immigrant on the verge of being torn from the only life she’s ever known. Rather than demonize those who would happily see her deported, though, the track recognizes the tragic humanity behind their closed-mindedness. “We don’t see half the people around us / But we see enemies who surround us,” Browne sings on the bilingual collaboration with Los Cenzontles’ Eugene Rodriguez. “And the walls that we’ve built between us / Keep us prisoners of our fear.”

“I started out wanting to talk about the conflict on the border,” Browne explains, “but the only way to talk about the conflict is to talk about the people living it, so it became about Lucina, a young woman Eugene and I both know. But the person who sees ‘enemies’ everywhere is also a human being, and what I sing has to be true for that person, too, because I’m not talking about them, I’m talking to them. Even if they don’t like me singing about a girl who came to this country illegally, I want them to care about her.”

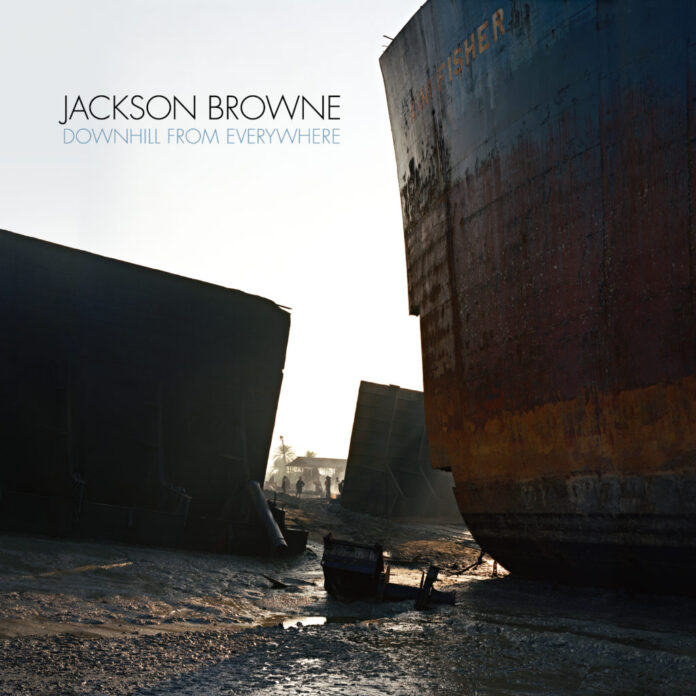

That’s not all Browne wants us to care about on ‘Downhill From Everywhere,’ which hints at the monumental scale of the work before us with its arresting cover art, a photograph from Edward Burtynsky’s surreal “Shipbreaking” series depicting Lilliputian humans engaged in the painstaking process of dismantling their own rusted, hulking creations. The soulful title track asks us to confront our personal and societal dependence on plastic and consider its devastating effect on the oceans; the Caribbean-flavored “Love Is Love” challenges us to expand our engagement with places like Haiti beyond the natural disasters and humanitarian crises that dominate our woefully limited understanding of the people and their culture; and the rousing “Until Justice Is Real” reckons with the kind of existential questions that define who we are and where we’re headed. “What is the future I’m trying to see?” Browne asks himself as much as anyone else. “What does that future need from me?”

“I think racial and economic and environmental justice are at the root of all the other issues we’re facing right now,” says Browne. “Dignity and justice are the bedrock of everything that matters to us in this life.”

And yet at no point on the album do we hear preaching from Browne, no lecturing or moralizing or pitting of neighbor against neighbor. Instead, the calls to action here are implicit, as are the warnings about the consequences of continued apathy. Browne relies on us to draw our own conclusions from the music, to connect the dots in the juxtaposition of imagery and recognize ourselves in the richly detailed renderings of modern life.

“As a songwriter, you want to catch people when they’re dreaming,” he explains. “You want to find a way into their psyche when they don’t see you coming.”

With ‘Downhill From Everywhere,’ Browne doesn’t just catch us while we’re dreaming, he challenges us to dream bigger. The songs are ultimately portraits—of people, of places, of possibilities—that appeal to our fundamental humanity, to the joy and pain and love and sadness and hope and desire that bind us all, not only to each other, but to those who came before and the generations still to come.