As the demand for festivals becomes ever greater, a potential supply-side problem has started to become apparent. It hints at how the music industry has changed rapidly over the past ten years, and how it may need to adapt.

Over the past decade sales of recorded music fell sharply. According to the BPI, an industry body, income from recorded music fell from £1.2 billion in 2004 to just under £700m in 2014. The fall has slowed in recent years, partly because of the increase in online streaming, which accounted for £115m in 2014. But other revenue streams have become far more important—particularly the live music industry. In 2011 it was worth £1.6 billion, according to PRS for Music, which collects royalties on behalf of writers and publishers.

Artists bag only 10% of the net profit from recorded music, but can command up to 90% of gross ticket receipts. And promoters can make money from large, captive audiences by charging eye-watering prices for food, merchandise and parking.

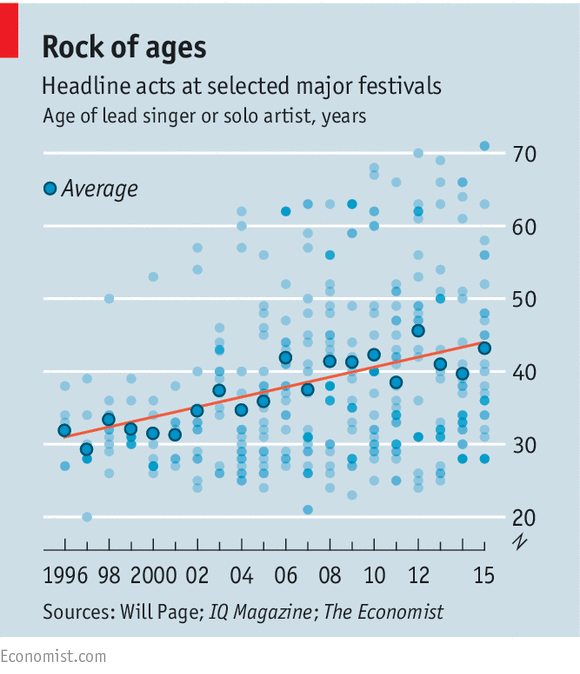

However, the popularity of festivals poses a problem. As they have grown in Britain so too have they blossomed in America, Asia and Europe. But the pool of artists who appeal to large, diverse crowds and have enough music to play for an hour or more has not increased at the same rate. This means that there are not enough big headliners to go around. Analysis by Will Page, the director of economics at Spotify, a streaming service, shows that the average age of headline acts at nine festivals in Britain has gradually risen (see chart). In the 1990s, bands in their mid-twenties, such as Radiohead, headlined at Glastonbury, points out Mr Page. Although exceptions exist—this year, the 28-year-old Florence Welch was drafted in at the last minute to headline the Friday slot—it appears to be getting rarer, he says.

Part of the reason for this may be that punters themselves are ageing: according to Festival Insights, an industry publication, in 2014 the average age of a festival-goer was 33. Promoters may be reacting to this by putting on older acts. But it also reflects a supply-side constraint in the market, says Chris Carey, a music consultant. Fewer small clubs and pubs exist for new young bands to start out, he says, and older bands are still keen to perform live in order to boost their coffers. This means that fledgling artists find it both harder to start a career and to muscle in to a headline slot once they have gained momentum.

Via The Economist